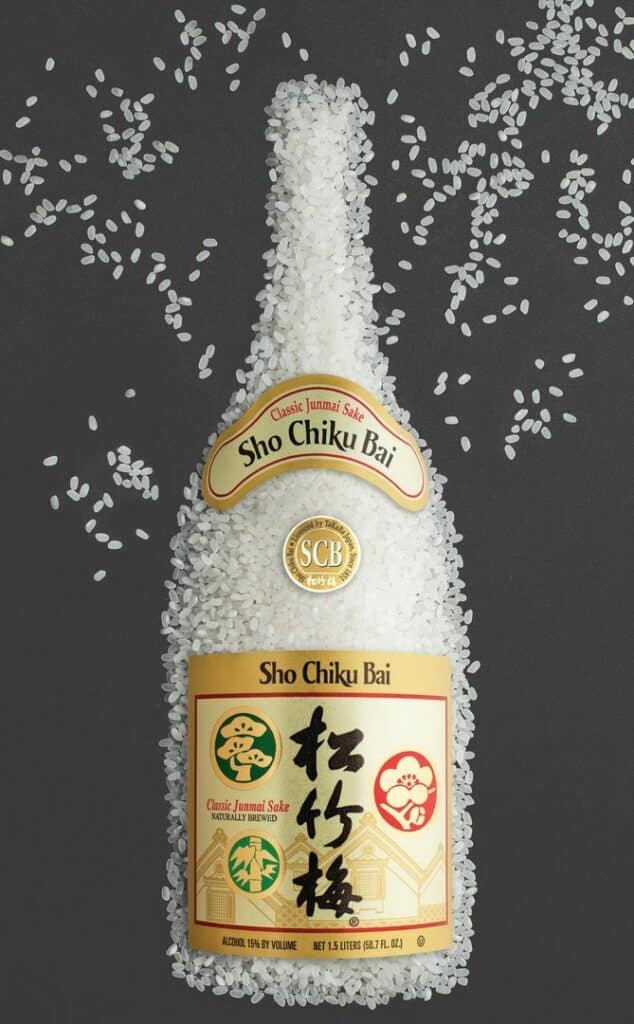

First of all, Takara’s Sho Chiku Bai brand sake is “Junmai sake”: brewed with only polished rice, water, koji, and yeast. Then, we brew both Junmai type (old-world type) sake and Ginjo type (20th century-new type) sake, which requires completely different techniques and methods for brewing.

What Are The Different Types of Sake?

Sake-making involves a centuries-old process perfected in the 17th century and carried on today.

Translated as “pure rice,” Junmai sake is made from rice, water, koji (rice mold) and yeast — nothing else. It’s the perfect drink if you’re looking to expand your culinary horizons.

- Junmai Sake vs. Aruten Sake: Official labeling purpose. Classification of sake based on ingredients, rice polishing ratio, and brewing method.

- Junmai Type vs. Ginjo Type: Old-world sake type vs 20th century-new sake type. Often used in differentiating the taste profile and characteristics of sake.

How Is Sake Brewed?

Rice Polishing

Rice polishing is the milling of whole, fresh brown rice grains down to their starch-rich cores.

Brewmasters can choose the precise rice-polishing ratio desired for their finished product. However, with Junmai sake, there are four broad categories — or ranges — rice can be polished down to. Each subsequent grade shaves additional weight from each rice grain, resulting in a wide variety of aromas and flavors.

- Junmai: Classic Junmai contains a rice polishing ratio within 70-100% of its original weight, known as its seimaido. Many Junmai fall into the former category (70% seimaido), reducing its kernels by roughly a third. The higher polishing ratios mean sake rice grains still hold various proteins, minerals, vitamins and lipids, contributing to sake with more body, higher acidity, and pronounced umami flavors.

- Tokubetsu Junmai: Tokubetsu Junmai has a rice polishing ratio of 60%. Like regular Junmai, the remaining proteins create a medium-bodied, savory-tasting sake than more polished types.

- Junmai Ginjo: Junmai Ginjo sake maintains rice polishing ratios also at 60%, sometimes less. This particular type of Junmai also introduces a special production method known as Ginjikomi, resulting in sake with a fruity and floral profile.

- Junmai Daiginjo: With a 50% or less rice polishing ratio, Junmai Daiginjo is the most milled rice grain used for Japanese sake. Junmai Daiginjo exposes the starch-rich kernel of each grain, creating delicate tasting sakes.

Polishing is performed by a special vertical milling machine made up of layers of spinning disks. Rice kernels repeatedly rotate through these disks, each time shedding minute layers until they reach the desired final polishing ratio. Overall, premium Ginjo polishing can take up to 10 hours to achieve 50-60% seimaido. Milling machines are designed to be gentle and exacting, minimizing intra-kernel friction and producing precise final polishing ratios.

Rice Washing

Newly polished rice moves onto the washing stage. During the washing stage, particles and impurities, known as nuka, get rinsed away from the kernels. This washing stage also removes any of a grain’s remaining outer bran. Performing careful rice-kernel washing ensures no nuka enter later-stage fermentation tanks, which would negatively affect sake’s yeast starter mash — and potentially taint the final taste. For that reason, rice washing is one of the most controlled steps in the entire Junmai brewing process.

In the United States, different types of sake are made from a premium California medium-grained rice called Calrose. Calrose is a hybrid between California long-grain rice and Japanese short-grained rice, first introduced in America by Japanese importers over a century ago. The medium-grained rice lends deep, robust sets of flavors to the sake and is a perfect base for brewing.

Rice Soaking

Immediately after washing, rice kernels are carefully soaked in controlled phases until properly rehydrated. Rice soaking prepares kernels for the next stage, steaming. For this reason, you’ll see some sake brewmasters referring to this stage as “pre-steaming” rather than soaking.

Brewmasters determine how long to soak kernels depending on the kind of sake they’re making, which is often determined by the rice polishing ratio. As a general practice, the more rice has been polished (for example, 30-40% final seimaido), the less it needs to soak. That’s because higher-polished grains absorb water faster — sometimes only needing a few minutes — compared to less-polished grains, which can require soaking overnight. So precise are these soaking timelines, in fact, that brewmasters are known to monitor soaking tanks with a stopwatch, ensuring grains steep down to the ideal second.

Note that high-quality water is required for all the washing, soaking and steaming phases of the sake brewing process. When making sake, that quality is typically found in “soft” water curated from a carefully selected source located near the brewery. For many producers, the quality of water used is as important as the quality of rice, yeast and koji itself.

Rice Steaming

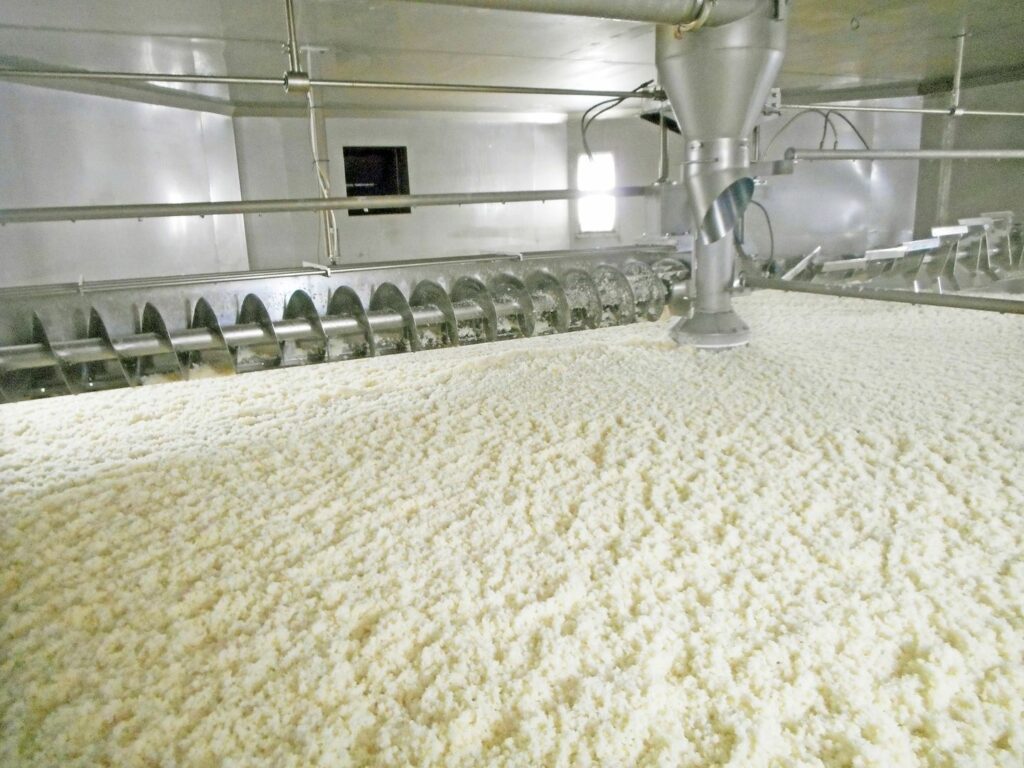

Next, rice enters the steaming stage. About 20% of the steamed rice will be used for making koji rice (kojimai), while the remaining 80%, called kakemai, becomes the base for the main mash.

The goal of steaming is to allow rice kernels to retain the perfect amount of water. They should grow firm on the outside yet become soft and supple at the center core, the perfect condition for producing the koji or being added to the fermentation mash. The key to successful steaming of rice is not to touch the rice directly with boiling water. In our facility, a modern machine continuously steams the rice as it moves along a conveyor belt.

For our Sho Chiku Bai Junmai Daiginjo production, we steam small batches of rice by the traditional method using a Koshiki-styled steamer, which is a deep vat for steaming rice.

At Takara Sake USA, all water used throughout the brewing process — including washing, soaking and steaming — is sourced from the Sierra Nevada Mountains, ensuring the purest and highest-quality water base possible for our products. Unlike with beer, sake brewers rarely alter water from its natural state. We do not distill or filter our water to remove its mineral components, nor do we add salt or any other flavor compounds. Instead, we find ways to work with the Sierra Nevada water as-is. This commitment to highlighting only local water and rice is not only more sustainable but allows our sake to truly represents its terroir.

Koji (Koji Rice) Cultivation

As mentioned above, about 20% of steamed rice is separated from the rest, then placed in special temperature-controlled rooms for cooling. After the rice reaches its desired temperature, brewmasters sprinkle koji spores on it. Koji mold is a rice-native mold essential for the breakdown of individual rice starch. The mold enzyme converts the rice’s starches into sugar and paves the way for fermentation. Koji rice (or just koji, to keep it short) making is considered to be one of the most important steps in the sake making process. Koji rice selection and preparation are extremely critical. Sake makers often choose a specific rice varietal or mold propagation style for a specific type of sake.

Koji propagation and cultivation are done in temperature-controlled, humid rooms for 36-48 hours. Brewmasters will frequently check the progress of their koji growth and will make adjustments to encourage optimal cultivation of koji mold.

Koji making for sake is an art form in itself. While there are three major strains of koji fungi, overall you’ll find brewmasters mostly cultivating yellow koji, or Aspergillus oryzae, for their sake brews. Yellow koji is also the foundation for making miso and soy sauce so essential in authentic and fusion Japanese recipes.

For our Sho Chiku Bai Junmai Daiginjo production, we handcraft koji in the traditional manner — manually repositioning trays and carefully nursing all steps of the koji cultivation.

Yeast Starter (Shubo or Moto)

Once koji reaches development, brewmasters move onto the next stage: creating sake’s yeast starter.

Starters (also known as shubo or moto) are a mix of the recently cultivated koji, a portion of steamed rice, additional water and yeast. The four-part mixture is added to a small, separate stainless-steel tank where it ferments for up to two weeks.

Sake yeast starters constitute the final stage of sake preparation. After creating this small, hyper-concentrated batch of yeast cells, brewmasters are ready to move onto making their signature creations.

Create the Main Mash (Moromi)

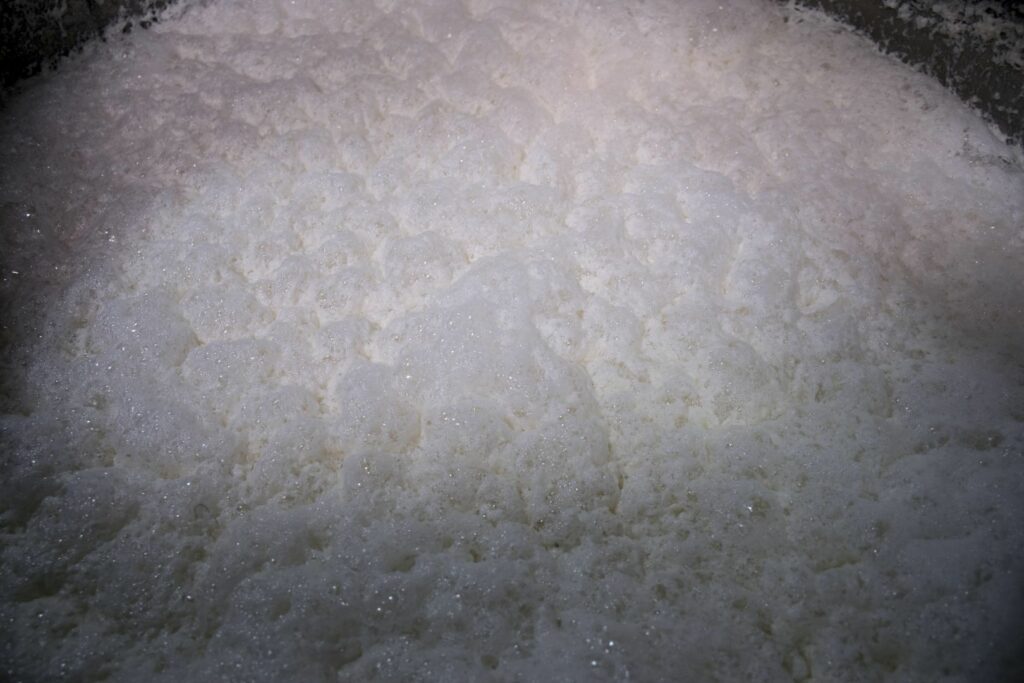

Sake mash, or moromi, is made by combining the fresh shubo (yeast starter), water, the steamed rice from Step Four and the koji rice from Step Five.

Moromi is combined in a large main fermentation tank. Over the next four days, more steamed rice, water, and koji rice will be added to the mix in a process called sandan jikomi. Incrementally adding these ingredients permits the living yeast and koji to fully (and flavorfully) integrate with the rice. It also inhibits the growth of unwanted microorganisms.

Once the four-day sandan jikomi stage ends, moromi remains in the fermentation tank for two to four weeks depending on the type of sake being produced. Remaining homogeneously sealed in the tank allows the sake to undergo its signature dual brewing process, with saccharization (sugar breakdown) and fermentation (sugar conversion to alcohol) taking place simultaneously. This is called a multiple parallel fermentation and it is very unique to the sake brewing method. The result is sake’s naturally higher ABV, around 20% when left unwatered.

Pressing

After two to four weeks, moromi is removed from the fermentation tank and transferred to a pressing machine known as the Yabuta.

Moromi runs through the Yabuta, passing down a series of pressurized, mesh-lined frames that separate the liquid sake from solid rice compounds called sake kasu (sake lees). Lees are residues leftover from fermentation that get removed from the majority of sake types, as they affect the texture and body of the sake. For example, our signature Nigori sake types, are pressed through more coarse meshes of yabuta bags to allow some of the rice solid to remain in the final liquid, which appears white.

There are a number of pressing techniques performed by sake brewmasters today. However, the safest and most consistent pressing method is to use a Yabuta.

For our Sho Chiku Bai Junmai Daiginjo, we use Fukuro-Shibori, drip separation method where newly fermented sake is poured into cloth bags and are hung up to allow the liquid to drip through the bag by gravity.

Filtration

Fresh sake is filtered to balance colors and flavors, and to remove any fine solids that slipped through the pressing process.

Sake filtration is performed through special charcoal filters. Charcoal, with its microscopic grooves, catches tiny solid particles like bland starch and rice proteins. The charcoal-powder lining is also antimicrobial, creating a safe and healthy system to run raw sake through without neutralizing its flavors.

Different sake breweries will adjust their filtration timelines and styles. Some even remain secret about filter layerings and techniques, since this step in the sake-making process is so instrumental to final flavors. However, once filtered, sake achieves its signature translucent, clear color and forms the basis of its rich, umami or fruity-floral taste.

Pasteurization

Most sake is pasteurized twice, once immediately after filtration and once before bottling, except for Nama-style, or micro-filtered sake.

During pasteurization, the liquid sake is heated between 140-150°F. Heat ends fermentation, but more importantly, it kills any bacteria that could compromise the taste, texture and shelf life of sake.

Sake is one of the few types of alcohol to receive this heat-based pasteurization step. Wine, for example, will contain added sulfates to maintain quality and extend the product’s shelf life. Likewise, other unpasteurized alcohol or spirits must be kept refrigerated to remain stable. Sake does not contain added sulfates or any other kind of preservative.

Aging

The majority of fresh sake is aged for three to six months before bottling and distribution. Sake generally should be drunk while it is still young – within a year of its production or less.

Like koji cultivation and pressing, sake aging techniques vary by region and brewmaster. The most popular method involves storing the newly pasteurized, clear and full-bodied sake in sealed stainless-steel tanks. These tanks are temperature-controlled and, in many cases, computer monitored for optimal conditions.

Aging sake mellows the sometimes aggressive, clunky umami-flavors natural at this fresh stage. Aging techniques don’t seek to change these flavors, but rather coax them into a refined, drinkable palate with layered secondary aromas and finishes.

Bottling and Distribution

From initial ingredient preparation to final quality assurance and bottling, sake has undergone a five to eight-month brewing process. This Japanese treasure is finally reaching its conclusion. Cheers!

Before bottling and the final pasteurization process (if desired), brewers blend water with the sake to reduce its 20% ABV down to the more approachable 15-16% ABV. Some sake, called Genshu (original sake), is left at its original ABV. Similarly, you can also shop for lower ABV sake for a lighter sake experience.

After the desired alcohol level is reached, sake is filled and capped into individual glass bottles. Sake labels are applied, then packaged, and ready for shipping.

Here are some ways to enjoy sake at home or use it in creative specialty cocktails:

- Try all four categories of Junmai sake. Each of the four types of premium Junmai sake are unique and vibrant experiences. Bodies, aromas, finishes, primary and secondary flavors transform across classic Junmai, Tokubetsu Junmai, Junmai Ginjo and Junmai Daiginjo. Sampling each kind gives you a well-rounded glimpse into this historic Japanese beverage — and lets you test your absolute favorite.

- Serve most Junmai and Tokubetsu Junmai sakes warm or at room temperature. For the best tasting experience, serve sake bottles labeled Junmai or Tokubetsu Junmai at room temperature (around 65-72°F) or warm (104°F). Warming your sake will amplify its nuanced umami flavors.

- Serve Junmai Ginjo and Junmai Daiginjo type sake chilled. For the best tasting experience of Junmai Ginjo and Junmai Daiginjo, serve chilled (50-60°F) to enjoy the delicate aromas and fruitier characters.

- Drink sake on its own or in cocktails. Junmai sake makes a fantastic base for cocktails. Reinvent classics or craft your own using sake’s unique fruity, floral, and savory notes.

Get Sake Delivered to Your Doorstep

We’re the number one seller and producer of imported and domestic sake in the United States, shipping directly to customers across the country.