The world of sake (seishu) is diverse and delicious. This Japanese rice-brewed alcohol is the country’s official national drink, and brewers have been perfecting it for at least 1,500 years based on a unique sake-making process using koji mold.

Brewing anything for so long will inevitably lead to variations, both in production techniques and specialty styles. Different types of sake have proliferated over the years, resulting in a unique classification system overseen by Japan’s National Tax Agency.

At its core, sake is categorized first by type, then by grade. We’ll explore this multi-branch family tree of Japanese sake so that you can understand this treasured alcoholic beverage’s unique lineage — plus discover your new favorite type of sake.

What Are The Different Types of Sake?

Overall, there are two major sake categories. All imported and domestic sake falls into one of these two categories:

- Futsu-shu/Basic: Futsu-shu sakes are known as basic, or ordinary, sake. Many compare Futsu-shu sake to commercial table wine, both in terms of availability and price. Ordinary sake comprises nearly two-thirds of all worldwide sake production and has a mild taste and body, with a subdued sweet palate and little-to-no acidity. Rice used to make Futsu-shu is at most polished to 70% and may or may not contain added brewer’s alcohol.

- Tokutei Meisho-shu/Premium: Tokutei Meisho-shu translates to “specially classified sake” and is considered a premium, more luxurious beverage compared to Futsu-shu sake. Overall, Tokutei Meisho-shu results in superior flavored and textured sakes and makes up one-third of worldwide sake production. According to national standards, premium sake can only be brewed using rice, water, yeast and koji, a form of fermenting mold. And, unlike the broad stamp of futsu-shu sake, premium sake is subdivided into eight specific classifications, known as grades. These eight grades of premium sake will be explored in-depth below.

Sake, like beer and wine, maintains a core set of defining taste, body, aroma and production characteristics. Yet each brand of sake will ultimately carry its own unique qualities, coaxed out by the kuramoto (brewery) and individual toji (brewmaster) who made it.

Premium Sake Grades Meaning

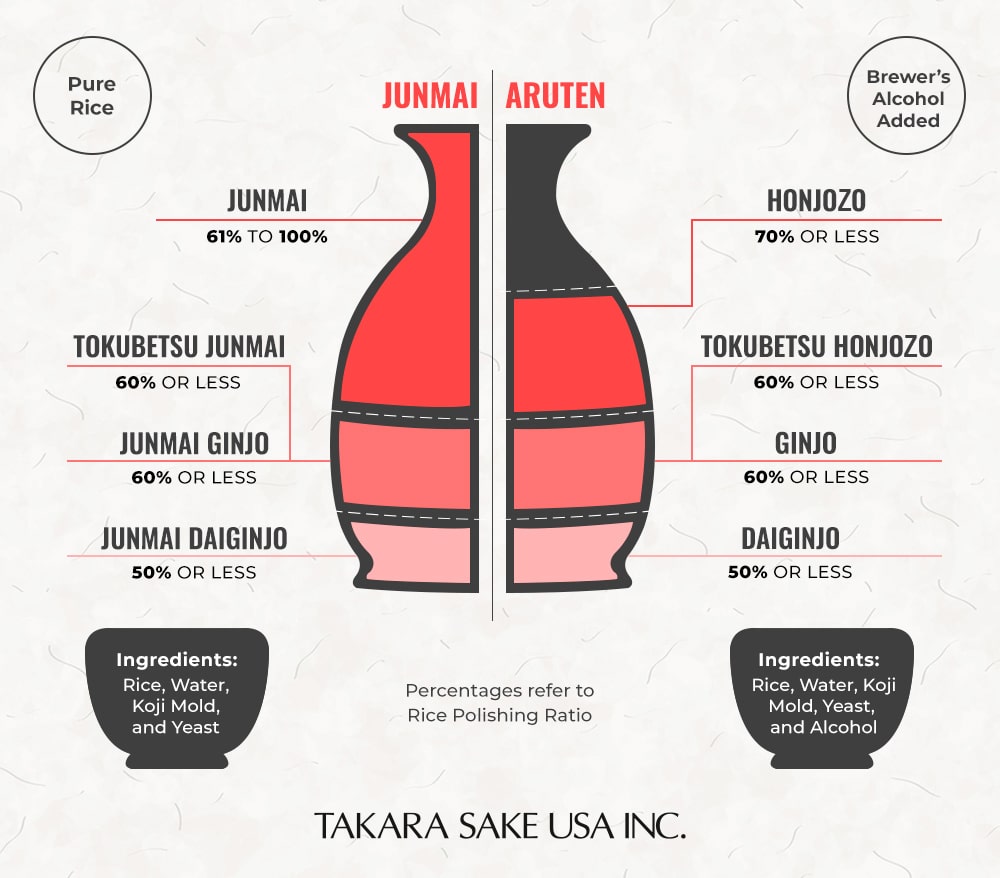

Premium Tokutei Meisho-shu sake is divided into eight grades. A sake receives its grade depending on its rice polishing ratio as well as whether it includes added brewer’s alcohol.

- Rice polishing: Rice polishing refers to the trimming of individual rice kernels, removing their outer layers to expose their starch-rich core. It’s these starches that will eventually convert into the sugar necessary for sake’s fermentation.

- Added brewer’s alcohol: For many reasons, Kuramotos add supplementary brewer’s alcohol to the moromi (main mash) during the sake production process. Brewer’s alcohol (jozo) must be neutral, derived from a natural agricultural origin. The amount of jozo must also adhere to the brewing standards outlined by the Japanese National Tax Agency to maintain its “specially classified” status.

Premium sakes that have added jozo are known as Aruten. Those without jozo — made only from rice, water, yeast and koji — are called Junmai.

What Are the Grades of Premium Sake?

1

Junmai

2

Tokubetsu Junmai

3

Junmai Ginjo

4

Junmai Daiginjo

5

Honjo

6

Tokubetsu Jonjozo

7

Ginjo

8

Daiginjo

How Are These Grades of Sake Classified?

Now that you’re familiar with premium sake’s two classifications (i.e., Aruten carrying brewer’s alcohol and Junmai, without brewer’s alcohol) let’s dive into the eight premium sake classifications themselves.

Each grade of sake provides a unique drinking and food-pairing experience. In particular, we’ll outline each premium sake category according to its:

- Origins

- Ingredients

- Preparation and production process

- Tasting profile

- Ideal food pairings

The word Junmai literally translates as “pure rice.” Therefore, bottles or brands labeled Junmai-shu are “pure rice sakes.” And that’s exactly what you get when you open one of these premium bottles, preparing yourself to experience sake’s true, focused palate.

Junmai is most commonly produced at medium-to-high temperatures brewed in quicker batches. This sake is also the only grade without specific rice polishing requirements. Brewers will typically use around 70% of the full rice kernel, coaxing Junmai’s concentrated grain and koji flavors. The result is a higher acidity, umami-forward or savory beverage with little to no residual sweetness.

Select Sho Chiku Bai Classic Junmai if you want a rich, full-bodied sake. Serve Junmai at room temperature or even warmed to bring out its mineral and often bread-like savory flavors.

- Junmai food pairings: Given its acidic but savory and umami-forward taste, pair Junmai sake with fatty meats like pork or ribeye steaks. Junmai also goes exceptionally well with high umami-veggies like mushrooms, asparagus and artichokes — all notoriously challenging liquor pairs.

- Other Takara Sake Junmai sake products: Sho Chiku Bai Extra Dry Junmai, Sho Chiku Bai Shirakabegura Kimoto Junmai, Sho Chiku Bai Shirakabegura Yamahai Junmai, Sho Chiku Bai Gokai Junmai, Sho Chiku Bai Kyoto Junmai

Tokubetsu means “special” in Japanese, and Tokubetsu Junmai certainly lives up to that label.

This no-added-alcohol sake requires a rice polishing ratio of 60% or less. The “special” touch to Tokubetsu Junmai, however, often comes in brewers using sake-specific rices, notably large-grain rice cultivated over the years to hold lower protein amounts and a higher water solubility. “Special” also describes a variety of noteworthy production methods brewmasters use to make Tokubetsu Junmai, along with its sake-specific rice varietals and additional specialty brewing practices.

Tokubetsu Junmai carries on many of the Junmai production techniques perfected in the 17th century. This legacy includes using “soft” water to brew sake mash, such as water from melted mountainside snow.

Given its rice polishing, Tokubetsu Junmai sake will have a lighter, crisper and more refined palate than a pure Junmai. Many are semi-dry and can be enjoyed cold, at room temperature or warmed, ideally in a decanter. The colder the serving, the more pronounced the crisp fruit flavors will be.

- Tokubetsu Junmai food pairings: You can’t go wrong pairing the dynamic, nuanced but ultimately versatile flavors packed inside Tokubetsu Junmai sake. Pair it with lightly oiled or fried foods, from Japanese tempura to American classics like fried chicken and fish. It also goes well with many Asian noodle dishes.

- Takara Sake Tokubetsu Junmai products: Sho Chiku Bai Tokubetsu Junmai, Sho Chiku Bai Kinpaku, Shirakabegura Tokubetsu Junmai, SHo Chiku Bai SHO Junmai Organic

Ginjo sake is made using highly polished rice (60% or less of the kernel left by weight) and particular kinds of yeast. These special yeasts have been cultured to be more expressive and fragrant than others found in different sake grades. In addition, Junmai Ginjo can be made using the Gin-jikomi production method, where the sake undergoes low-temperature fermentation across a long period of time using sake-specific rice varietals selected by the brewmaster.

As a result of the low-temperature fermentation, select sake rice varietals and Ginjo-style yeasts, Junmai Ginjo is delicate and fruitier than other Junmai sakes. Junmai Ginjo sakes are also notable for their distinct floral aroma.

Serve the clean, perfumed and smooth Junmai Ginjo sake at room temperature or chilled. If you serve it too hot, its unique flavor composition gets muddled by the heat.

- Junmai Ginjo food pairings: Junmai Ginjo is a match made in heaven for classic Japanese sushi and sashimi, plus other international fares like burritos, tandoori meats, tajine and German spätzle. Its fruity and flowered upticks harken to Japanese pear, lychee, melons and jasmine, with velvety finishing notes. This composition works well with Ceasar, chicken and tuna salads, light fare like frittatas, cheese plates and wraps and light proteins like tofu or shrimp.

- Takara Junmai Ginjo products: Sho Chiku Bai Premium Ginjo, Takara Sierra Cold, Sho Chiku Bai SHO Junmai Ginjo

Junmai Daiginjo production is similar to Junmai Ginjo — but goes one step further. With the Daiginjo technique, the highest amount of rice is polished away, resulting in kernels at 50% or less of their original weight. At this size, a kernel’s innermost starchy core is exposed. Brewmasters can then get to work converting pure rice starch into sugar for fermentation while minimizing the proteins and minerals in their base, resulting in a sake grade with a truly delicate flavor finesse.

Daiginjo is a highly precise brewing process involving time-intensive, low-temperature fermentation. It’s also brewed from premium sake-specific rice varietals selected by brewmasters to create the final flavors, bodies, and aromas he or she seeks. As a result, Junmai Daiginjo is considered the highest-grade sake.

Bottles of this premium sake variety will carry exquisite floral ginjoka complemented by rich, lush, and refined fruit flavors and a subtle umami finish. Top-shelf Junmai Daiginjo will carry a fine, velvety body that lingers in the mouth just long enough to tease the next sip.

- Junmai Daiginjo food parings: Shellfish, sushi with white fish, uni, poached chicken breast, brie and cambozola cheese are brightened by Junmai Daiginjo’s lush profile. For that same reason, it goes great with popular dishes like pizza, tacos and even spicy Thai curries. Avoid rich umami flavors, heavy soy sauce or miso.

- Takara Junmai Daiginjo products: Sho Chiku Bai Junmai Daiginjo, Sho Chiku Bai Shirakabegura Junmai Daiginjo, Sho Chiku Bai REI Junmai Daiginjo

Honjozo is one of four sake grades in the aruten classification. This means producers can add special all-natural brewer’s alcohol, also known as jozo, to their bases and still maintain its premium-grade classification.

Adding jozo-alcohol before the pressing stage of sake production serves a few purposes. First, it boosts the sake’s ABV and shelf life. Sake ABV levels on average hover between 15-21%, with many undiluted aruten brands on the higher end of that scale (17-21%). Yet no reputable sake producer partakes in jozo simply to create a higher ABV. More likely, they do so for the second and more significant purpose — to add complexity to their sake’s entire profile.

Brewer’s alcohol draws out deeper flavors and aromas from sake’s fermenting rice mash. It can also lighten the sake’s overall body and tends to produce dryer beverages with longer, robust finishes.

Honjozo sake experiences mild 70% or less rice polishing. Many sakes in this grade will be pleasantly acidic, light in body but savory as they linger.

- Honjozo food pairings: Honjozo sake’s acidic but earthy palate is a great partner for grilled meats, from steaks and burgers to chicken breasts, as well as grilled or sauteed veggies and kebobs.

Similar to the Tokubetsu Junmai with which it shares part of its name, Tokubetsu Honjozo is a more refined kind of Honjozo with added brewer’s alchohol and a few unique production techniques.

Producers of this sake grade adhere to Tokubetsu’s 60% or less rice polishing levels, sometimes using specialty sake rice like those with low protein amounts, low minerals and high water solubility.

Together, Tokubetsu Honjozo’s high-quality rice base, polished kernels and kiss of added alcohol create a zesty sake with a medium-full body and lasting mouthfeel. Expect notes of caramel, black tea, Asian pear, banana, cedar and sourdough, plus unique flavors drawn out by a brand’s brewmasters.

- Tokubetsu Honjozo food pairings: Pair Tokubetsu Honjozo sakes with salty soups, stews and ramen bowls. It also makes a good companion to spicier dishes like chilis, curries and jerk chicken.

In taste, body and aroma, Ginjo sake is a breath of fresh air.

Few sakes present the fragrant, bright but approachable layerings of fruit with florals and acidity. Top-shelf Ginjo brands in particular balance this elegant trio by adding jozo alcohol. Deepened by that alcohol, Ginjo often offers an elegant array of tart, sugar and bread notes without veering too heavy or acidic. The 60% or less polished rice mash used as its base helps ground this grade’s light mouthfeel and body, with sips that fade into a smooth finish.

To experience Ginjo-grade sake at its best, serve chilled or at room temperature — particularly to reap its full floral bouquet.

- Ginjo food pairings: Ginjo-type sake can pair widely with light and mild foods.

As its name suggests, Daiginjo-grade sake is made in the ginjo style but in greater scale. This means highly polished rice leveled down to 50% or less of its original weight with exposed, starchy cores ready to sweeten and intensify this grade’s unique profile.

Many brewmasters seek to harness those intense ginjoka aromas with their Daiginjo blends. Perfumed notes on the nose easily complement the fruity and even jammy flavors brought out by drinking this particular grade of sake, emphasized when brewer’s alcohol is added to the finely trimmed fermented rice mash.

Select Daiginjo sake for a lush, juicy sake that can be enjoyed solo or to lighten a range of dishes. Serve chilled.

- Daiginjo food pairings: Daiginjo is great with popular Asian foods like pho, dim sum and mild pad thai.

Additional Sake Terms and Classifications

The eight categories of premium sake above constitute a world of flavors onto themselves. You could easily dedicate yourself to discerning your favorite sake type from these eight classifications and still only scratch sake’s surface.

Yet the true sake connoisseur doesn’t stop at knowing only sake grade meanings. Consider these additional important sake terms and categories. When included on a label, these titles denote either a specialty sake style or a niche production process differentiating its end product from others.

Muroka is unrefined sake. Most commercial sake brewing processes involve filtration, where raw sake is pressed and fined after fermentation to remove lees and lingering starches and proteins. Muroka sake is pressed post-fermentation but is not charcoal or carbon filtered, resulting in a straw yellow rather than clear final liquid.

- Muroka-style Takara products: Sho Chiku Bai Junmai Daiginjo

All sake must undergo a pressing step, where its fermented rice mash is run through a filter to remove unwanted particles before pasteurization and bottling.

The majority of sake types undergo a fine-mesh pressing process, eliminating all rice residue. Nigori, however, is passed through a coarse filterer. This allows undissolved rice kernels and particles to make their way into the final product. Nigori sake, i.e. coarsely filtered sake, is identifiable due to its milky white color.

- Nigori-style Takara products: Sho Chiku Bai Nigori Silky Mild, Sho Chiku Bai Nigori Crème de Sake, Sho Chiku Bai SHO Ginjo Nigori

Sparkling sake comes in two forms: Carbonated or bottle-fermented. Carbonated sparkling sake is more common, mild and stable, made when the brewmaster infuses carbon into rice mesh while inside a pressurized fermentation tank. Bottle-fermented sparkling sake, however, traps carbon dioxide after the product has been bottled. It is usually unpasteurized and varies in carbonation amount and flavor.

- Takara Sparkling Sake products: Sho Chiku Bai Shirakabegura MIO Spakling Sake

Nama is the Japanese term for unpasteurized liquids. Instead of classic heat-based pasteurization, Nama sake instead passes through a series of micro-filters to help sterilize the end product.

- Nama-style Takara products: Sho Chiku Bai Organic Nama

Genshu is sake that has not been diluted after the fermentation process. The word genshu in Japanese translates to “original.” Genshu sake, therefore, is made only of the original, post-fermentation rice liquor and is not watered down for a lower ABV before bottling.

- Genshu-style Takara products: Sho Chiku Bai Junmai Daiginjo

Kimoto (Junmai) represents the most traditional method of sake-making established in the 17th century. It involves using a fermentation starter made from vigorously pounded steamed rice paste called yamaoroshi. Kimoto Junmai is known to display complex but well-balanced flavors, particularly highlighting its umami and acidity. This revered sake-making technique has seen a resurgence in recent years, particularly amongst sake connoisseurs looking to experience the beverage in one of its most authentic historical forms.

- Takara’s products: Sho Chiku Bai Shirakabegura Kimoto Junmai

Yamahai is another sake production method similar to Kimoto. It seeks to bring out the deep, bold and umami-forward flavors of its rice mash starter, however it was developed after the Kimoto process. The Yamahai-style of sake brewing was popular until the turn of the century, where more rapid-brewing methods like Sokujo became the norm. However, just like with the Kimoto-style, Yamahai Junmai has been reintroduced to the markets in recent years and is especially popular for its bold flavors and body.

- Takara’s products: Sho Chiku Bai Shirakabegura Yamahai Junmai

Get Sake Delivered to Your Doorstep

We’re the number one seller and producer of imported and domestic sake in the United States, shipping directly to customers across the country.

Discover the world of sake from the comfort of your home by exploring Takara Sake’s online catalog. We’re the number one seller and producer of imported and domestic sake in the United States, shipping directly to customers across the country. Explore our online inventory of premium Junmai sake and bring 1,500+ years of brewing culture into your home.